|

Sophia on the web

A Resource Guide for Philosophy Students

Created by Jennifer Leslie Torgerson, MA

This

page last modified: September 18, 2012

©

copyright, 1997 - present

http://philosophyhippo.net

Plato

c. 428 (427)

– 348 (347) BCE

Bibliography

F.

M. Cornford.

Plato and Parmenides. (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill

Company, no date).

__________,

Before and After Socrates. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999 [1932]).

__________,

From Religion to Philosophy: A Study in the Origins of Western

Speculation. (Mineola, NY: Dover Books, 2004 [1912]).

Frederick

Copleston, S.J., A History of Philosophy: Book

One. (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1985 [1944]).

Walter

Kaufmann, Philosophical Classics Volume

I: Thales to Ockham, 2nd

Edition. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1968 [1961]).

A. A. Long, Editor; The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek

Philosophy. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Plato. Great

Dialogues of Plato; W. H. D. Rouse, Translator. (New York, NY: Mentor Books, 1956).

__________. The

Republic and Other Works; B. Jowett, Translator. (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1973).

__________. The

Trial and Death of Socrates; G. M. A. Grube,

Translator. (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 1975).

__________. Plato: The Collected Works, including the Letters;

Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Editors. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994 [1961]).

The works of Plato

|

Apology (Defense of

Socrates)

Crito

Phaedo

Charmides

Laches

Lysis

Euthyphro

Menexenus

Lesser Hippias

Ion

Gorgias

Protagoras

Meno

Euthydemus

|

Cratylus

Phaedrus

Symposium (The Dinner

Party)

Parmenides

Sophist

Philebus

Timaeus

Critias

Laws

Letters

---

the following may not be authentic

Epinomis

Greater Hippias

|

Some details of Plato's life:

Plato was a child when his father Ariston died. His

mother married his uncle who was a good friend of Pericles. Plato's mother

had a brother, Charmides (car-my-dees), and a cousin Critias,

who were prominent in politics in the days of the oligarchy that ruled Athens

at the end of the Peloponnesian War. Plato may have known Socrates all of his

life, but did not actually come under his spell until, he was close to

twenty, and thereafter devoted his life to philosophy. The Athenian hatred of

Socrates had certainly been fed by the fact that he was friends with members

of the oligarchy. But this is no reason to assume that they (Meletus, Anytus, and Lycon) made those charges against him (Socrates) due to

their hatred of the oligarchs. Plato is very disillusioned with democracy for

putting Socrates to death, but he doesn't like oligarchs much either.

Plato's objective idealism and the Theory of Ideal Forms

To avoid the difficulties inherent within subjective

idealistic positions (such as that of "to be is to be perceived" of

Berkeley, which will be discussed later in the semester), Plato developed an

objective idealistic theory of reality. Objective idealism is the view that

the world out there is Mind communicating with our human minds. An example of

this type of metaphysical theory of objective idealism is that of Plato's

theories of Being and Becoming and the Ideal Forms. Plato held that the

material, phenomenal world (the world of appearances) is in a state of flux

attempting to emulate (unsuccessfully) the Ideal Forms (the noumenal world of reality). The Forms exist independently

of the consciousness. The noumenal world is the

true permanent world of reality.

The Two Worlds of Being and Becoming:

- Forms in the world of Being

are absolute, noumenal, unchanging,

transcendental, eternal, intelligible, archetypal, perfect, and

objective. Examples are: (1) Form

of Justice, (2) Form of Table, (3) Form of Man.

- Things in the world of Becoming are relative,

phenomenal, changing, space-time world, sensible, copied, imperfect, and

subjective. Examples are: (1) legislation, trials,

(2) this table, that table, (3) Linus,

Sally, and Lucy

critique of objective idealism:

Because the problem of the cause of common perceptions

was evident to Plato, he claimed that these common perceptions are derived

from the Ideal Forms. But how do we get knowledge from the eternal Ideal

Forms? How is this interaction possible? This was a problem that Plato was

well aware of, as the dialogue Parmenides discusses this very issue. Consider

the relationship between man and men. There is an essence, a third man, which

demonstrates what is similar between a particular man and men in general. But

what of the relation between man, men, and this third man; isn't there a need

to describe what essence the man, men, and the third man have in common, the

fourth man? This can go on, as it is an infinite regression. But we will get

back to this discussion when we begin Aristotle, as this is Aristotle's

criticism, (or the Achilles' heel) of Plato's theory of the Ideal Forms.

Note how Plato's theory of Being and Becoming is a

refutation of the relativistic position of Protagoras. If all things are in a

constant change, then true knowledge of reality is not possible. Plato's view

of the changing world of Becoming (appearances) is similar to the Heraclitean flux, but it is the noumenal

world of Being which resembles the One of Parmenides. Remember the law of

non-contradiction: (1) what is and cannot not be

and (2) what is not and cannot be?

This description can be said of the world of Being,

that it is eternal and will never cease to be. This is Plato's description

(as in the Timaeus 27d- 28a):

- Being is that which always is and has no becoming,

and is that which is apprehended by intelligence and reason and is

always in the same state.

- Becoming is that which never is and is that which is

conceived by opinion with the help of sensation and without reason and

is always in a process of becoming and perishing and never really is.

But in the Republic (479d- 480a), Plato presents

a slightly different description of the world of Being and Becoming:

- The Form of the Good [the

most important Form; it maintains and sustains the others, and it

also is the vehicle via which knowledge of the Forms reaches the realm

of Becoming (see the Analogy of the Sun)]

- nonbeing [nothing;

non-existence]

This view is also called the view of the One over the

Many, and is Plato's solution to the problem of the one and the many of the

Pre-Socratics.

critique: presented by Aristotle,

(Meta. 990 b [15]):

...[A]nd according to the "one over many" argument

there will be Forms even of negations, and according to the argument that

there is an object for thought even when the thing has perished, there will

be Forms of perishable things [...].

There would too need to be Forms of all things

horrible. What of change? Is there a Form of change? How about

vomit? It doesn't sound so perfect anymore.

What is a form?

form: comes from the Greek word eidos which

literally means form, or the shape and structure, or the essence of a thing;

it is what makes a thing a part of that particular class of things. The

Forms are in fact the eidos that are ideos (ideas). The idea of form is

attributed to Pythagoras.

Plato thought that this Idea of the essence of a thing

existed in another plane, or world which was absolute and unchanging: the

world of the Ideal Forms. The Forms exist independently of the consciousness,

and would continue for all time, even if there was no one alive to apprehend

the Forms. Some call this other realm "Plato's heaven".

Theory of the Ideal Forms: (a definition) it is the belief in a transcendent world of eternal

and absolute beings, corresponding to every kind of thing that there is, and

causing in particular things their essential nature.

The theory of the Ideal Forms is based upon Plato's

belief that there existed two separate worlds:

(a) BEING: The transcendent (noumenal)

world of the Absolute, perfect, unchanging Ideal Forms of which The Good is

the primary and the source of all the others such as Justice, Temperance,

Courage; and

(b) BECOMING: the phenomenal world (the world of

appearances) composed of things in a state of flux attempting to (but

unsuccessfully) emulate (imitate, participate in, partake of) the Ideal

Forms. The phenomenal world is the world of our sensuous, ordinary, everyday

experiences which are changing and illusory.

The world of the Eternal Forms is real, true, permanent

world of reason. Abstractions, such as redness, equality, and humanness that

one can conceive and recognize in a variety of things prove that the Forms

exist.

From Euthyphro (6c-e):

Euthyphro, who is prosecuting his father for impiety (for murdering his slave),

is questioned by Socrates about the essence of piety. Socrates says to Euthyphro: "I wanted you to tell me, what is the essential form of piety which makes all pious actions

pious?"

And with such a Form, all actions can be judged to as

whether they resemble the essence contained in the Form, or if they do not.

This is the objective nature of Plato's theory of the Ideal Forms. All

instances of those actions which are pious in the world of Becoming can be

compared to the one and only Form of piety in the world of Being. The problem

of how the Form imparts this essence upon particular things is an issue which

Plato never resolved, although he was well aware of the difficulty (as

discussed prior in the criticism of objective idealism).

Two different explanations of the Forms:

(1) In the Euthyphro:

(6c-e)

Sensible things are copies of the forms, or they

"participate in" the Forms.

(2) In the Phaedo:

(100c-e)

Forms are only a "relation to" or

"present in" sensible objects.

"Forms are causes of both Being and

Becoming." -Aristotle, Metaphysics 991 b [2-3].

It is just this type of ambiguity that Aristotle will

seize upon as the "Achilles' heel" of Plato's theory of the Ideal

Forms.

Blending of the Forms:

Things are able to participate in more than one Form.

Consider all things rectangular: tables, doors, chalkboards, etc. Each thing

has its own essence: "tableness", "doorness", "chalkboardness";

but they all share in a common essence: "rectangleness".

Same with all living things; each has their own essence: "catness", "humanness", "treeness"; but they also share the essence of

"living thingness".

Accidental features of the Forms:

Things may possess accidental properties, such as

color. Color may be an accidental property of a thing if and only if changing

a particular thing's color does not change the thing's essential nature to be

a member of that class of things (such as red and green apples- in either

case they are still members of the class of apples).

Degrees of Knowledge: the divided line

(Republic, 509d-511e)

|

|

METAPHYSICS

|

EPISTEMOLOGY

|

|

|

|

higher

Forms; Forms of ideas;

Forms without embodiment

i.e., beauty, justice, temperance, goodness, etc.

|

understanding

(knowing why)

Pure reason

|

|

|

BEING

|

mathematical Forms and Forms of

things (tables, chairs, etc.)

Forms

of things with embodiment in the realm of Becoming

|

reason

(knowing

how)

|

KNOWLEDGE

|

|

BECOMING

|

sensible

objects

|

perception

(true

belief)

|

OPINION

(or belief)

|

|

|

(obscured)

images

|

imagination

(false

belief)

|

|

from: Copleston, History

of Philosophy vol. 1.

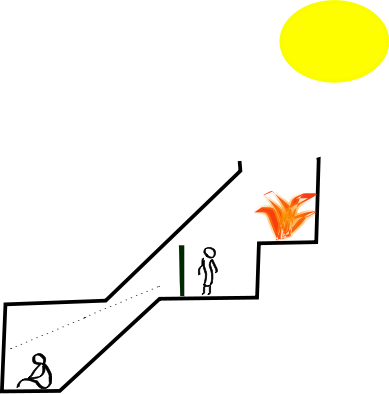

The allegory of the cave

(Republic,

Book VII, ¤ 19)

or 514a- 516c

allegory

interpretation allegory

interpretation

INSIDE THE CAVE (BECOMING)

(1) The shadows on wall of cave are equivalent to

BELIEF (images, etc.)

(2) The roadway and fire are equivalent to the ordinary

visible objects

DAYLIGHT REALM (BEING)

(1) shadows and are equivalent to the mathematical

WORLD and reflections OF objects KNOWLEDGE

(2) The trees, mountains, etc., are equivalent to the

Forms etc.

(3) The sun is equivalent to the essential Form of the

Good

The essential Form of the Good

The essential Form of the Good is like the sun, in that

the Good is the source of ultimate knowledge, much like the sun is the

ultimate source of life. For the Good to be the source of knowledge it cannot

be a Being, but it must transcend the world of Being. Therefore the Form of

the Good is beyond knowledge. (Remember Kant's phenomenalism?)

Two main points to the analogy of the sun to the Form

of the Good:

(1) The sun illuminates the physical world in the same

way that the Form of the Good sheds light upon the other Forms, or

intelligible world.

(2) The sun actually is the cause of existence and

sustaining existence in the physical world. Without the sun all would perish.

Similarly, without the Form of the Good, there would be no other Forms. There

would be no other Forms because the Form of the Good is their cause or

source. The Good maintains the being and truth of all other Forms, and hence

the sensible world.

Sight:

The Sun is the source of Light, and so makes objects

visible, and allows the eye to see.

Knowledge:

Goodness is the source of Truth, and so makes The Forms

intelligible, and allows the mind to know.

Knowledge,

hence is a kind of sight or vision

Plato's rationalism and his theory of recollection

One of the most important questions in philosophy is

"What is the basis or source of knowledge?" Epistemology (which

comes from the Greek words: episteme = knowledge, and logos =

the study of).

The two classical epistemological theories are

rationalism (from the Latin word ratio = reason) and empiricism (from

the Greek word empeiria =

experience).

epistemology: the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature, source,

limitations, and validity of knowledge.

empiricism: the view that all human knowledge is acquired from sense experience

(via the 5 senses: touch, taste, smell, hearing, and sight) or a

posteriori which is Latin for "that which follows after." All

knowledge is acquired after sensible experience, or post-experientially.

rationalism: the view that all human knowledge is acquired through reason as the

primary source, prior (or a priori which is Latin for "that which

precedes") and superior to sense experience.

Theory of Recollection

Plato suggests that we are already born in possession

of knowledge of which we are not conscious of but will readily recollect (recollectus in Latin) if carefully prompted.

Plato has Socrates illustrate this in a dialogue called the Meno. Socrates extracts the answer to a geometrical

problem out of a slave boy who knows no geometry.

Socrates asks Meno:

"What do you think, Meno? Has he answered

without any opinions that were not his own?" Meno

replies: "No, they were all his." [...] Socrates concludes:

"So a man who does not know has in himself true opinions on a subject

without having knowledge." (85 c).

critiques of rationalism:

(1) Because the self-evident truths of rationalism are

not tangible, and are by nature in the mind, rationalists tend to disagree on

so-called "self-evident truths".

(2) Rationalism fails to account for the increase in

human knowledge. Refute critiques as Plato would.

theory of

innate ideas: The theory that the "fundamental ideas or principles are

built right into the mind itself and require only to be developed and brought

to maturity." Because Plato held that the source of our knowledge is

innate idea, Plato was a rationalist.

But how is it possible for one to have innate ideas in

one's mind when born? In order to hold that knowledge is innate idea, Plato

developed a belief of the immortality of the soul. A great deal of Plato's

ideas come from Pythagoras, especially the " dualistic juxtaposition of

body and soul, and the conception of the body (soma in Greek) as the

tomb (sema in Greek) of the soul; the

belief in the immortality of the soul; the doctrine of the transmigration of

souls; the idea that knowledge and a philosophic life are required for the

salvation of the soul; the notion that one might design a society that would

be an instrument of salvation for its members; the admission of women into

this society; the suggestion that all members should hold their property in

common; and finally the division of man into three basic types- tradesmen

being the lowest; those whom the competitive spirit and ambition are highly

developed, a little higher; and those who prefer contemplation, the most

excellent." (from Walter Kaufmann, Philosophical Classics (pp. 10-11).

Plato and his view of the State

The state is the individual at large (BK 2 Republic)

Plato held that there must be one moral code for the

individual and the State, because the State is composed of individual men and

exists for the leading of the good life. Because justice is determined by the

Ideal Form of Justice, both the individual and the State must live under the

influence of the eternal code of justice. In his work the Republic, Plato is not concerned with

describing actual states, but in describing what the nature of the Ideal

State is, so that actual states can conform themselves as best they can.

In the seventh Letter (written to Dionysius II)

Plato describes how he first

had a bad experience with the Oligarchy of 404 BCE, and then with the

restored Democracy.

Plato's Ideal State consists

of three classes of men (excluding slaves):

(1) Artisans at the bottom,

(2) Auxiliaries, or military class over them,

and

(3)

Guardians, or Guardian at

the top.

The classes as outlined

represent justice:

(1) The wisdom resides in the small class of

Guardians;

(2) Courage of the state is in the class of

Auxiliaries; and

(3)

Temperance

is represented by the due subordination of the governed to the governing.

Political injustice consists

of meddling, which leads to one class interfering with the affairs of

another.

While the higher two classes

share property in commune, the artisan class retains their property and the

family unit. But due to the training and breeding of the Auxiliaries and the

Guardians, their family units are destroyed. This is done to ensure that the Guardian

class and the Auxiliary class owe their duty to the State, and not their

family. In effect the state has become their family, providing food,

shelter, education, and protection.

In the eighth

book of the Republic Plato develops

a sort of philosophy of history. The perfect State is the aristocratic State

(literally, "rule of the best"). Those individuals best able to

rule the aristocratic State are those who can apprehend the eternal Forms

(Goodness, Truth, Justice, etc.); philosophers are able to apprehend the

eternal Forms. Therefore philosophers are best suited to rule, or be

'philosopher-kings." This is a type of elitism, or rule by a select few.

Plato thought that women could too be rulers; but not quite the equal.

"And if so, my friend, I

said, there is no special faculty of administration in a state which a woman

has because she is a woman, or which a man has by virtue of his sex, but the

gifts of nature are alike diffused in both; all the pursuits of men are the

pursuits of women also, but in all of them woman is inferior to man." (Republic 455e).

But if the higher two classes

of an aristocracy combine to divide the property of the lowest class and

reduce them practically to slavery, then aristocracy turns into timocracy (a state in which the honor attached to the

position of ruler is sought by the ambitious with intrigue, rather than

trust).

Love of wealth grows until timocracy turns into plutocracy or oligarchy (rule by a

few rich individuals). Political power is dependent upon property

qualifications.

A poverty stricken class is

created by the greed oligarchs, and in the end the poor dispel the rich and

establish democracy (rule by the people). Democracy is the worst form of

government according to Plato because "the government of the many is in

every respect weak and unable to do either any great good or any great evil

when compared to the others, because in such a State the offices are parceled

out among many people." Republic

(303 a [2-8] ).

But the love of liberty and

majority rule leads to, by way of reaction, to tyranny or dictatorship

(absolute rule of one individual). At first the champion of the people

executes a coup d’état (surprise attack of the state), and turns into

a tyrant.

The Ideal State must be a

true Polity. Democracy, oligarchy, and tyranny are all undesirable because

the laws passed by such states are passed for the good of a particular class.

States which have such laws are parties, and not polities, and their notion

of justice is simply unmeaning. But in a true Polity, the laws passed are for

the good of the whole State.

The similarity of the state to the soul ~ the state as

the individual at large

|

class

of state

|

faculty

of the soul

|

virtues

|

|

|

Guardians

|

represent

reason

|

and wisdom.

|

\

|

|

Auxiliaries

|

represent

the spirited element

|

and courage.

|

Justice

|

|

Craftsmen

|

represent

the appetitive element

|

and temperance.

|

/

|

Summaries to the remaining Platonic dialogue excerpts

PHAEDO

This dialogue explains the nature of the soul

(65a-67b).

There are three faculties of the soul according to

Plato:

(1) Reason- cognition; knows the good from the

bad (rational element)

(2) Spirited element- will (with consciousness)

(3) Appetites- (appetitive) animal desires, lust

(those desires we do not control)

"We have found, they will say, a path of

speculation which seems to bring us and the argument to the conclusion that

while we are in the body, and while the soul is mingled with this mass of

evil, our desire will not be satisfied, and our desire is of the truth.

For the body is a source of endless trouble to use by reason of the

mere requirement of food; and also is liable to diseases which overtake and

impede us in the search of after the truth; and by filling us so full of

loves, and lusts, and fears, and fancies, and idols, and every sort of folly,

prevents our ever having, as people say, so much as a thought. [...]

Moreover, if there is time and an inclination toward a philosophy, yet

the body introduces a turmoil and confusion and fear into the course of

speculation, and hinders us from seeing the truth: and all experience

shows that if we would have pure knowledge of anything we must quit the body,

and the soul herself must behold all things in themselves: then I

suppose that we shall attain that which we desire, and of which we say that

we are lovers, and that is wisdom, not while we live, but after death, as the

argument shows; for if while in company with the body the soul cannot

have pure knowledge, one of two things seems to follow-- either knowledge is

not to be attained at all, or if at all, after death. For then, and not

till then, the soul will be in herself alone and

without the body. In this present life, I reckon that we make the

nearest approach to knowledge when we have the least possible concern or

interest in the body, and are not saturated with the bodily nature, but

retain pure until the hour when God himself is pleased to release us."

(66b-67b Phaedo).

"Then, Simmias, as the

true philosophers are ever studying death, to them, of all men, death is the

least terrible."(67e Phaedo).

Some other points expressed in the Phaedo:

1. Morality cannot be based on emotion. (69b-c)

2. Opposites generate opposites. (70e)

3. The process of generation and change is

between opposites; and takes place in two stages for example there is going

to sleep as well as waking up--- there is a coming to life and a coming to

death. (71c-71e).

4. Why is there a need of an ordered process (a

generation of change)? Change would turn what is to what is not and all

would cease to be including change itself. (72b).

5. The fact that souls are immortal provides a

time in which there was perfect knowledge to be recollected. Nothing in

this world is perfect. Perfect equality does not exist in this

world of change, yet we still have a concept of equality. (72e-77b).

6. The soul is not a composite (78c).

7. Differences between body and soul (80b):

|

SOUL

|

BODY

|

|

divine

|

mortal

|

|

no

parts

|

parts

|

|

no

change

|

change

|

|

does

not disintegrate

|

disintegrates

rapidly

|

|

invisible

|

visible

|

8. The myth of Er

(82b-88c):

We may have the happiest of states, which practices

philosophy and reason, "no one but a fool is entitled to face death with

confidence, unless he can prove that the soul is absolutely immortal and

indestructible. Otherwise everyone must always feel apprehension at the

approach of death; for fear that in this particular separation from the body

his soul may be finally and utterly destroyed."

9. The things in this world partake in the forms:

"The consider the next step, and see whether you share my

opinion. It seems to me that whatever else is beautiful apart from the

absolute beauty is beautiful because it partakes in absolute beauty, and for

no other reason." (100e)

MENO

This dialogue is a demonstration of how the theory of

recollection works. The theory of recollection was discussed earlier on

this web page.

"And, I, Meno, like what

I am saying. Some things I have said of which I am not altogether

confident. But that we shall be better and braver and less helpless if

we think that we ought to enquire, than we should have been if we indulged in

the idle fancy that there is no knowing and no use in seeking to know what we

do not know; -- that is a theme upon which I am ready to fight, in word and

deed, to the utmost of my power."

Meno diagrams

PHAEDRUS

"Real existence, colorless, formless, and

intangible, visible only to the intelligence which sits at the helm of the

soul, and with which the family of true science is concerned, has its abode

in this region. The mind then of deity, as it is fed by inheritance, is

delighted at seeing the essence to which it has been so long a stranger, and

by the light of truth is fostered and made to thrive, until, by the

revolution of heaven, it is brought round again to the same point. And

during the circuit it sees distinctly absolute justice, and absolute

temperance, and absolute science; not so much as they appear in

creation, nor under the variety of the forms to which we nowadays give the

name of realities, but the justice, the temperance, the science, which exist in

that which is real and essential being." (247d-248).

"For the soul which has never seen the truth at

all can never enter into the human form." (250a).

THE REPUBLIC

Some of the main elements of The Republic have been already discussed

on this web page.

Here are few more main ideas or notes, organized by book:

BOOK 2:

The rings of Gyges story

(359c-361)

BOOK 3:

the metals

"It was quite natural that I should be, I said,

but all the same hear the rest of the story. While all of you in the city are

brothers, we say in our tale, yet God in fashioning those of you who are

fitted to hold rule mingled gold in their generation, for which reason they

are the most precious-- but in the helpers silver, and iron and brass in the

farmers and other craftsmen. And as you are all akin, though for the

most part you will breed after your kinds, it may sometimes happen that a

golden father would beget a silver son and that a golden offspring would come

from a silver sire and that the rest would in like manner be born of one

another. So that the first and chief injunction that the god lays upon

rulers is that of nothing else are they to be such careful guardians and so

intently observant as of the intermixture of these metals in the souls of

their offspring, and if sons are born to them with an infusion of brass or

iron they shall by no means give way to pity in their treatment of them, but

shall assign to each the status due to his nature and thrust them out among

the artisans or the farmers. And again, if from these there are born

sons with unexpected gold or silver in their composition they shall honor

such and bid them to go up higher, some to the office of guardian, some to

the assistantship, alleging that there is an oracle that the state shall then

be overthrown when the man of iron or brass is its guardian. Do you see

any way of getting them to believe this tale?" (415 a-c).

|

metals

for each class

|

|

CLASS

|

METAL

|

|

Guardian(s)

|

gold

|

|

Auxiliaries

(assistants)

|

silver

|

|

Craftsmen

|

brass

|

|

Farmers

|

iron

|

BOOK 4:

"Then, as I was saying, our youth should be trained

from the first in a stricter system, for if amusements become lawless, and

the youths themselves become lawless, they can never grow up into

well-conducted and virtuous citizens." (425 a)

BOOK 5:

1. The only difference between men and women is that

the males are stronger and the women weaker. (451e-452e).

2. The natures of men and women differ; hence

they should have different pursuits. (453e).

3. Women can be guardians, if they are wise, or

properly suited to rule. (453).

4. Men and women doctors have the same nature.

(454d).

5. Women not married, but held in common;

children will not know their parents. (457d).

6. Selective breeding is used to produce the

"perfect flock." (459-460).

7. Breeding done in the prime of life (20 for

women and 30 for men). (460e).

8. "And the city whose state is most like

that of an individual man. [...] The same, he said, and, to return to

your question, the best-governed state most nearly resembles such an

organism." (462d-e). This is an organic view of state.

9. Guardians do not own property. (466).

10. Children are taken to observe war, early in

life. (467).

11. There is a distinction between knowledge and

opinion. (477e).

12. "And likewise of the great and small

things, the light and the heavy things-- will they admit these predicate any

more than their opposites? No, he said, each of them will always hold

of, partake of, both. Then is each of these multiples rather

than is not that which affirms it to be? They are like the jesters who

palter with us in a double sense at banquets, he replied, and resemble the

children's riddle about the eunuch and his hitting of the bat-- with what and

as it sat on what they signify that he struck it. For these things too

equivocate, and it is impossible to conceive firmly any one of them to be or

not to be or both or neither." (479c-d). Hence we are caught between

being and non-being (in becoming).

BOOK 6:

the divided line

BOOK 7:

the allegory of the cave

the analogy of the sun

PARMENIDES

1. This is a very difficult dialogue, full of

information. It contains a debate between Parmenides, Zeno, and Socrates

regarding the problem of the one and the many.

It is most noted for the critique that Plato is showing

of his own position.

The critique is called the problem of the third man.

thing> form

of thing> form that thing and the form share> form that the 3rd form,

the form, and the thing share> ... ad infinitum. (133a-b).

2. The Forms do not exist in this world. (133c).

Because the Forms are not in this world, it is not

clear what essential nature is shared by all men, as it truly is in and of

itself.

3. God does not have knowledge of particulars,

but only of the Forms, and hence is not omniscient. (134e).

4. Plato reduced to absurdity the notion of

picture theory. (165c-166a).

PHILEBUS

This is another difficult dialogue containing many

concepts, including an excellent discussion of the life of pleasure, the life

of pain, and the life of pleasure and pain, as well as a discussion of techne (craft).

Plato's solution to the problem of the one and the many

is the view of the one over the many. (18e).

Know thyself. (48d).

TIMAEUS

The creator of the universe is all good. (29e-30b).

This dialogue explains the origin or generation of the

cosmos.

Everything in the universe has been created by some

cause. (28b).

|